Leland Watershed Water Quality Monitoring Project

The goal of this project is to provide the Leland community with the information and training necessary to monitor water quality within their watershed. The water quality data produced by citizen monitoring will be used by local and state agencies to understand, protect, and restore water quality in the Leland watershed.

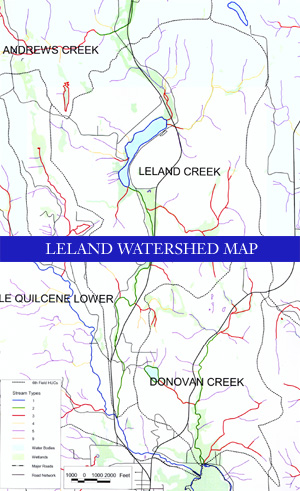

The Leland Watershed is located in the foothills of the Olympic Mountains in eastern Jefferson County of Washington State. The watershed rests in the rainshadow of the Olympic Mountains.

These mountains block major North Pacific storm systems from reaching the Leland watershed and as a result the annual precipitation is only about 75cm. This is less than half of the annual precipitation in other portions of the Olympic Peninsula. The watershed begins five miles north of the town of Quilcene. It includes Lake Leland, Leland Creek and the lower portion of the Little Quilcene River, which empties into Quilcene Bay and Hood Canal.

Lake Leland

The Leland Watershed starts 190 feet above sea level at Lake Leland. Lake Leland is a boot shaped lake about 107 acres in size. It has a drainage area of 5.71 square miles, which includes 25 tributaries, most of which are small. There is one major inlet at the north end of the lake. The lake has a maximum depth of 20 feet and a mean depth of 13 feet. The 2.75 miles of shoreline remain relatively undeveloped; however, this is sure to change as more houses are being built close to the water's edge.

Leland Creek

Lake Leland has only one surface outflow, Leland Creek, which is located at the south end of the lake. Leland Creek is 6.55 miles in length and drains and area of about 11.3 square miles. From the lake, Leland Creek passes through a wetland area infested with reed canary grass. It then flows past a non-functioning fish weir and under Leland Valley Road West. There is a small culvert under the road but during the winter and into spring, the water level rises to a point where the Creek ends up flowing over the road. After crossing Leland Valley Road, the creek meanders southward. It flows through alternating sections of open reed canary grass fields and thinly wooded land on the west side of Highway 101. During this journey, development along the bank of Leland Creek becomes somewhat denser with an increasing number of homes and cleared land. The creek also increases in volume along its course as several tributaries join it. After meandering for about two miles, the creek flows under Highway 101 through a box culvert. During higher flows the water behind the culvert often gets backed up and flow appears to stop almost completely. Once passing under the culvert, Leland creek continues for about one mile more before it empties into the Little Quilcene River.

Little Quilcene River

The Little Quilcene River drains a total of about 16,400 acres of mostly forested land, and the final stretch of this river is a part of the Leland watershed. Leland Creek enters the Little Quilcene River a couple miles before the system empties into the northern end of Quilcene Bay and Hood Canal. During these last miles, the Little Quilcene River maintains a fairly straight path with some gentle meanders. The banks are scattered with homes and trailers, and this development has left some sections of this portion of the river devoid of natural riparian habitat. The mean flow of the Little Quilcene River is about 38.5 cfs.

Vegetation

The vegetation in the Leland watershed is mostly native and typical of the Pacific Northwest. Trees found in the area include Douglas fir, western redcedar, western hemlock, red alder, big leaf maple, and vine maple. The native shrubs and ferns in the area include rhododendron, salmonberry, red elderberry, evergreen and red huckleberry, Oregon grape, salal, and swordfern. In addition to these commonly found trees and plants, there are several rare plant species that have been identified in the Leland watershed. The "Lake Leland Integrated Aquatic Plant Management Plan" states, "according to the natural heritage Information System, a state sensitive plant species, bristly sedge (Carex comosa), occurs in a wetland at the south end of Lake Leland and Leland Creek. A rare forested wetland type (western redcedar/western hemlock/skunkcabbage) has also been identified in the northwest quarter of section 23 and is designated Priority 1 for protection by the Natural Heritage Program." The Leland watershed is also home to several nonnative and invasive plant species including reed canary grass and the aquatic plant, Brazilian Elodea.

Wildlife

The Leland watershed provides a habitat for a variety of wildlife. Both osprey and eagles are known to nest in the area, and according to the 1998 DFW "Priority Habitats and Species Report", established spotted owl territory exists on the southwest side of the watershed. Other commonly sighted birds include pileated woodpeckers and great blue herons. In the winter migratory birds such as trumpeter swans, Canada geese, and other waterfowl can also be found in the watershed.

In addition to providing a home to numerous species of birds, the Leland area hosts a variety of other animals such as black tailed deer, red fox, coyote, black bear, and cougar. The Leland watershed also provides habitat for several species of freshwater and anadromous fish. The thriving large mouth bass population that Lake Leland supports makes it a popular destination for sport fishermen. A 1996 WDFW report states that the lake contains the highest density of large (> 12 inches) largemouth bass in Western Washington. Other fish, which can be caught in the lake, include bluegill, black crappie, yellow perch, and rainbow trout. In addition, the Leland watershed provides habitat for two salmon species.

Salmon in the Leland Watershed

The Leland watershed has historically been a breeding ground for chum and coho salmon as well as steelhead. Area residents such as Hector Munn still recall the days when these fish swam all the way up to Lake Leland during their migration to spawn. This migration ended by the early 1950's for primarily two reasons. In about 1948 local farmers, in cooperation with the Soil Conservation District, dredged the upper reaches of Leland Creek in order to get the land back into use. This dredging destroyed much of the salmon habitat in the creek. Then in the early 1950's the Department of Fish and Wildlife constructed a fish weir (sometimes called a fish gate) at the outlet of Lake Leland into Leland Creek. The fish weir was intended to keep trout in the lake for fishermen by preventing the fish from going down Leland Creek. However the weir also kept salmon from entering the lake and effectively ended their migration into Lake Leland. The fish weir is no longer functioning. However, other developments within the watershed over the past few decades have taken its place in inhibiting the return of salmon to Lake Leland and upper reaches of Leland Creek.

Threats to Salmon Habitat

There are several factors in the Leland watershed which have destroyed much of the salmon habitat and continue to threaten that which is left. These include culvert blockages, lack of adequate riparian habitat, and possible repercussions of development.

Culvert Blockages

In order for spawning salmon to make the journey from Quilcene Bay up to Lake Leland and for juveniles to make the trek back down, they must pass through several culverts. The first culvert they come to is under State Highway 101 where it crosses Leland Creek. In 1992 the State assessed this box culvert and determined that it was 100% passable at that time. However, since 1992 the culvert has developed a sizable blockage as evidenced by the frequent backup of water behind it. A more recent assessment done by WDFW Project Manager, Mike Barber, during November of 1999 determined that the culvert blockage at least partially inhibits salmon passage. This blockage was noted in the WDFW's database and scheduled for improvement. The blockage has since been removed and water was flowing freely through the culvert as of January 7, 2000. It is important that this type of maintenance continue on a regular basis to ensure that the culvert is passable by fish.

Those salmon that are able to pass under highway 101 continue up Leland Creek. Some begin leaving the creek along the way in order to travel up smaller tributaries where they will spawn. One such tributary is located at milepost 3 of Leland Valley Road. Here a culvert blockage once again inhibits the passage of salmon. This blockage was recognized by state fisheries and the tribes and is currently being addressed by the Jefferson County Public Works Department.

Those salmon that continue up Leland Creek into Lake Leland will face one final culvert obstacle. Just before Leland Creek connects with the lake, it flows through a small culvert under Leland Valley Road. During low flow months this culvert seems adequate to handle the water passing through. However, during higher flows the water gets backed up and eventually flows over the road. This flooding occurs during more than half of the year and often makes the road impassable for residents. It is speculated that the flooding and backup of water also poses a barrier to fish passage. Some claim that any fish trying to get up to Lake Leland would be able to swim over the road during flood stage. While this is probable, it is important that the culvert and flooding be assessed and improved not only because of the possible fish blockage, but also because of the inconvenience it causes to residents who want to use the road.

Reed Canary Grass

The growth of reed canary grass at the head of Leland Creek has contributed to the destruction of salmon habitat. Reed canary grass, Phalaris arundinacea, is a non-native, perennial grass that propagates through underground rhizomes and seed. It can be identified by its tall (often 3-6 feet), erect stems and flat blade-like leaves, which are typically 4-14 inches long and 0.5 to 1 inch wide. The grass flowers from June to September, producing flower heads 3 to 16 inches long. Reed canary grass is competitive and persistent. It spreads aggressively and invades moist areas such as meadows, lake shores, stream and canal banks, and wetlands.

The upper stretches of Leland creek were originally planted with reed canary grass in order to feed cattle. Unfortunately the long-term effects of this species were not known at that time. Susan Harlow, a professor of UVM, writes, "Reed canary grass has been elbowing its way into wetlands and roadsides since it was first cultivated in the United States as an animal feed 150 years ago. When it's small and tasty, the grass is good forage for animals. But once it gets large, and it's one of the tallest forage grasses, cattle turn up their noses at Phalaris arundinacea." The grass has invaded almost the entire upper half of Leland Creek and has replaced the natural riparian vegetation in this area.

Reed canary grass can adversely affect salmon in three main ways. First, because of its rapid and unrestrained growth, reed canary grass can clog stream channels and prevent the passage of fish. The grass also threatens salmon by lowering dissolved oxygen levels in the stream it occupies. As the grass fills the stream channel it dies and begins to decompose. The decomposition process uses oxygen, which is taken from the stream. The result is lowered dissolved oxygen levels that often cannot support salmon. Finally, reed canary grass is highly competitive with native plant species in wetland areas. Its creeping root system forces out other plants and reduces the natural riparian habitat along streams where it has invaded. This is detrimental to salmon that depend on riparian habitat for the shade, channel structure, and food it provides.

Development

The Leland watershed is not an area of rapidly increasing development; however, the community is growing. The effects from this growth, as well as from existing land use activities, have caused threats to salmon migration. These threats are specifically caused by activities such as septic system use and deforestation.

Many homes in the Leland watershed use septic systems. If constructed and maintained properly, septic systems are very effective and do not threaten water quality. When septic systems fail, the domestic wastewater ends up filtering directly into the groundwater, stream or lake. This pollution greatly reduces water quality both for domestic use and as habitat for salmon and other wildlife. Without proper education regarding septic system installation and maintenance and regular water quality monitoring, it is almost impossible to insure that septic systems are working properly.

Another threat to water quality in the Leland watershed is the loss of riparian habitat due to deforestation and development. As previously mentioned, much of the natural riparian habitat along Leland Creek has been replaced by non-native reed canary grass. In addition, several sections of the bank of the Little Quilcene River have been cleared, and pastures and homes have replaced the natural stream side vegetation. This loss of riparian habitat threatens the water quality of the stream and the lives of the salmon for several reasons: increased water temperatures and erosion, decreased large woody debris, and increased runoff from various land use practices.

There are ways to reduce and even eliminate these threats to salmon habitat and water quality in the Leland watershed. By developing an action plan we can restore the watershed to the natural and healthy environment that once supported large runs of salmon and steelhead.